Geopolitics, migration and food

by Lucio Caracciolo

The aim of this research is to highlight the often underestimated link between food and migration. This link is investigated here by analysing every aspect that affects it, starting with geopolitical and economic contexts, demographic trends and the impact of climate change. These are all decisive push factors in migrations, a structural phenomenon in the world we inhabit and in which future generations will live. Every crisis-based approach to migratory flows is therefore destined to produce limited or even negative results. It would be equally disastrous to tackle these flows through national agendas that are aimed at unloading the problem onto weaker countries and/or those most exposed to these flows. Only a global strategy, guided by awareness that the migratory issue affects all humankind and is destined to profoundly influence the planetary ecosystem, can allow balanced and responsible management.

The following analyses are, in particular, concentrated on the Mediterranean area, understood in the broadest possible way: the fault line between migratory flows coming from sub-Saharan Africa and heading for Europe. African migratory routes, which often follow the ancient transit roads used for trade of every kind, starting with food and the other natural products, evolve constantly due to the changing intensity of push and pull factors, as well as the enforcement policies of local governments, which are effectively subsidised by some European countries. The significant revenue flowing to African populations from migrations – which occur mostly (about 90%) within the continent’s borders, with only a small minority which travels to Europe via the Mediterranean – encourages criminal and terrorist groups to intercept and manage, to their own advantage, the trafficking of human beings. The media’s emphasis on the Mediterranean perspective of the migratory phenomenon often ends up obfuscating its deeper causes and fuels a climate of emergency in global public opinion. It is also for this reason that we have tried here to favour a scientific, analytical approach in the hope of contributing to a better informed and therefore calmer public debate.

With this in mind, the food-migration link is therefore set within the framework of a study of the multiple factors that influence the movement and food culture of individuals and populations, regarding both countries of origin and host countries. Additionally, as the latest World Food Programme report clearly shows, there is a particularly strong link between migrations, food and conflicts: refugee outflows per 1.000 population increase by 0.4% for each additional year of conflict, and by 1.9% for each percentage increase of food insecurity, while “higher levels of undernourishment contribute to the occurrence and intensity of armed conflict” (WFP 2017).

In the study of the countries of origin, dedicated specifically to sub-Saharan Africa1, the emphasis falls on the causes of a vicious circle involving nutrition and migration. The links that form this chain include skyrocketing demographic growth, inadequate nutrition, interruption of physical growth and of the development of cognitive abilities, and the spreading of chronic diseases with obvious consequences on productivity and the economic conditions of individuals and the community. The result is a Malthusian trap: poverty produces malnutrition (if not hunger) and high infant mortality which in turn promotes high fertility, which generates poverty. The cycle then contributes to pushing the younger members of the population to leave their lands of origin in search of a future that will allow them to break it once and for all. They do this to guarantee the nutrition and therefore the survival, within a family context that is often quite extended, of those who cannot or do not wish to abandon their homes, their lands of origin and their customs. Hence also the importance, attributed here within the framework of recommendations to investment schemes for remittances of which a significant proportion should be reserved for agricultural development, and therefore nutrition, in the countries of origin.

Regarding the host countries, food turns out to be above all a central factor in the integration of migrants in European host countries. Food has increasingly become a distinctive element of the identities (including religious identities) of individuals and communities. The spreading of eating habits and customs from migrant origin countries, particularly from Africa, is changing the European cultural panorama. It is not only a question of diet or preferences, but of the introduction of new cultural codes through the ingredients, rules and cuisine imported by immigrants. This is increasingly reflected by the food industry and markets in Europe. It is therefore essential for integration projects to rely not only upon basic linguistic and cultural aspects, but also on food, enhancing the contribution of the food customs of migrants, while also encouraging in this field exchanges and contributions through this medium between long-standing and newly-forming communities. This must especially be done between second generations, where the decisive ‘game’ concerning integration is played out. One cannot ignore the difficulties posed by this approach, because among European populations the differences between nutrition cultures can be exploited by those rejecting every possibility of co-existing with those coming from countries that are perceived as socio-culturally “distant”, with little regard to the geographic meaning of the word.

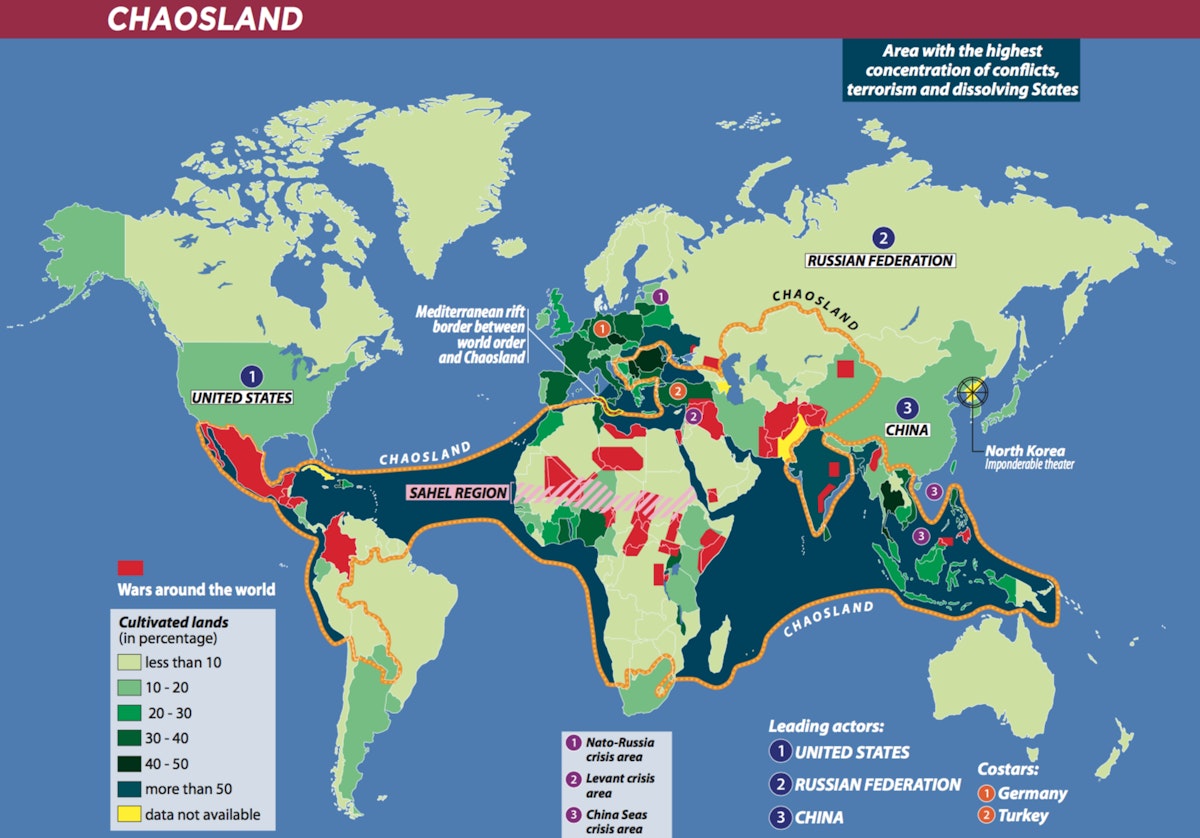

To seize the importance of the challenge linked to migration and food, it is therefore useful to start from the geopolitical context that conditions it. One perspective to contextualize the Mediterranean as a critical junction is through the geopolitical representation of the world in two broadly defined regions: Orderland and Chaosland 2.

Here we have two neighbouring worlds defined as much by current asymmetries such as by their long-standing economic, political and socio-cultural linkages. Consequently, the Mediterranean is increasingly an area of friction, of potential conflict and of migrations, which, in the long term, will have a significant impact on Europe’s culture and identity.

Europe, after the 2008 financial and economic crisis, is facing a number of challenges. There is a widespread perception that member states do not share the same interests. There is a visible lack of trust in European institutions and even in the possibility of a common approach to common challenges – starting with migration flows – leading to a tendency to unload problems on one another rather than address them together. The Brexit referendum in the UK may be considered by future historians as the kick-off point for a major reshuffling of the European geopolitical landscape.

As for Africa and the South-East Mediterranean, these are areas struggling with the greatest instability factors – wars, terrorism, widespread poverty, climate change and its consequences on agriculture and food, and most notably, soaring migration. The latter occurs largely within the region itself, although the media tends to focus on the South-North flows, thus depicting a kind of “invasion” of Europe.

The primacy of demography

Among the relevant push factors regarding migrations, demography is by far the most important, particularly in the medium and long term, as we show in our analysis on the five main regions making up the Euro-Mediterranean area. Africa’s population already stands at 1.2 billion - by mid-century the number will have doubled, and it will be four times as high by 2100. On the Mediterranean’s northern shore, Europeans number about 700 million (500 million live in EU nations, plus about 200 million in Russia, Ukraine and other eastern European states), with a downward trend predominating, so much so that Europeans are expected to amount to about 650 million by the end of this century, as the global population peaks at about 11 billion. One should also consider that the median age in Europe is about 45, while in Africa it is less than 20. Younger people, especially facing the threat of conflicts and living in miserable environments, will look for any opportunity that may give them some hope for a better future. This is why, in order to assess the impact of migration in the Mediterranean, a thorough consideration of Africa’s economic prospects – both in terms of asymmetries and opportunities – is also necessary.

Managing urbanization and climate change

Another significant phenomenon and migration driver related to demography is the global urbanization trend. For the first time in history, since 2007 an increasingly large majority of the planet’s population lives in urban environments. Everywhere, huge megacities are attracting people from the countryside. In Africa there are two major examples of this trend: Lagos (Nigeria) and Cairo (Egypt) 3. This concentration of people in relatively small areas can bring about a serious decrease in order and stability in these mega-cities as well as a demographic draining of the countryside, with – among other things – an immediate impact on food production. Combining these demographic trends with climate change, one already sees that in most African countries, while demand for water rises exponentially, water supplies are becoming far less reliable. This is another quite significant push factor for North-South (but also South-South) migrations as well as a possible cause of conflict, considering the relevance of land and water acquisition activities in Africa (which will be addressed more fully later). Emphasizing interdependence is key also in tackling climate change, given that it will impact also on food systems in all countries involved in Trans-Mediterranean migration, including European countries of transit and destination.

State fragility and criminal networks

In this context, the impact of tensions and wars in Northern and sub-Saharan Africa, but also in the Levant and the Greater Middle East, is contributing to the disintegration or fragmentation of states, some of which now exist only on paper, such as Libya, Somalia, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. Among other consequences, this means a lack of “phone numbers” available to the leaders of the European states who are interested in finding partners able to monitor and control migration flows. At the same time, human trafficking is a driving factor in most African and Middle Eastern economies. In many cases, governments or individual local leaders are actively participating in migrant smuggling.

South-South migration

As we highlighted, one should not forget that migrants reaching European shores across the Mediterranean represent but a tiny fraction of the total amount of migration flows worldwide: dominant narratives tend to underrepresent the fact that the largest share of migration from Africa and Asia is not directed to Europe, but remains within their regions of origin. According to available statistics, 84% of the migrant population originating from West Africa moves inside the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) area, while diaspora communities from the Horn of Africa are largely absorbed by neighbouring countries, such as Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia and Yemen, and not by Europe (Malakooti et al. 2015; IOM 2017). South-North migration, in other words, is the exception, while South-South migration remains the rule.

The disruption of food systems

While the push and pull factors of migration trends are varied and multifaceted, one can confidently state that food systems are part of the picture. In the last decades, major migratory flows from and within Africa have been prompted by the disruption of traditional food systems, as a result of climate change and droughts (such as in Sahelian countries in the 1970s); inadequate food policies (as in Ethiopia in the 1980s); or controversial trade agreements (as in many West African countries since the 1990s). On the other hand, the lack of workers in the agricultural sector in countries on the Northern shore of the Mediterranean has provided a pull factor for migratory flows and has fostered the exploitation of cheap labour. Therefore, more international cooperation is needed to implement all the actions proposed for African agriculture and agro-businesses by the Agenda 2063 of the African Union Commission.

A long-term challenge

All things considered, it is necessary to come to terms with the fact that migration flows are unstoppable. Corridors may be closed for some time (as now applies to the Eastern Corridor, from Turkey to Greece), but not forever. And in any case, migrants will open new routes, often with help from professional smugglers and mafias.

A comprehensive research agenda on food and migration, which includes the analysis on Africa’s migration hubs, can be helpful in managing the long-term geopolitical challenge of interdependence between the two shores of the Mediterranean. Throughout the history of the Mediterranean, food routes and migrant routes were frequently intertwined. A closer look at both shores of the Mediterranean helps us to assess our present challenges.

On the one hand, in Africa’s migration hubs, it is key to break a vicious circle where poverty nourishes hunger, malnutrition and high infant mortality. Therefore, increasing global attention to Africa’s role (where various “Marshall Plans” and “Investment Plans” aim to enhance Africa’s immense growth potential) needs to be focused on breaking this Malthusian trap and turning it into opportunities for African agriculture and human capital, consistent with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

On the other hand, European societies are facing and will face a strategic issue, that of integration. How many foreigners are we able and willing to absorb in our already heterogeneous nation-states? How can we manage the interaction between cultures, customs and religions that are destined to become increasingly significant – and very visible – in the near future? And more specifically, what will the impact of migration be on food cycles and cultures both in countries of origin and those of destination? To this goal, best practices of food integration in Europe need to be analysed and shared.

We believe these fundamental issues demand a far-reaching and interdisciplinary debate. This is why we have gathered experts and consultants hailing from different fields (demography, climatology, economics, migration studies) to explore the “migration-food” nexus in a geopolitical framework, through specific essays and contributions. In this framework, the Sustainable Development Goals for the 2030 Agenda are a constant reference, given their close relationship with food and migration.

We consider this a first step in the collaboration between the geopolitical analysis provided by MacroGeo and the Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition Foundation, which analyses the economic, scientific, social and environmental factors connected to food. In his address at Food and Agriculture Organization for the 2017 World Food Day, Pope Francis reminded that “the relationship between hunger and migration can only be tackled if we go to the root of the problem”.

There is an increasing international awareness on the relevance of food and migration for our sustainable future. Specifically, trans-Mediterranean migration flows are an ongoing challenge which requires constant attention by analysts and policymakers. This is why, in the near future, we plan to gather more perspectives in this exploratory field, including from anthropologists, historians, urbanists, activists, and to include more research on the voices of migrants themselves and on policymakers from countries of origin. Also country-based cases studies and the sharing of best practices at the local level might help understand further this topic, its paradoxes and its opportunities, in dialogue with all the relevant stakeholders. To keep up to date with the evolution of the analysis of the migration-food nexus, please visit our website www.foodandmigration.com

Migration is a structural reality all over the world, and in the case of the Mediterranean, is here to stay. Dealing with this phenomenon, its perception and its consequences – anticipated or unexpected – is an important challenge for our societies that demands the best tools. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the migration-food nexus is an important investment today that will bear great dividends tomorrow

Notes

1 We focus mostly on Sub-Saharan Africa to underline its relevance in terms of future demographic and economic growth.

2 The fault line between Chaosland and Orderland does not imply a value judgement or a necessity. Its purpose is to identify different and intertwined geopolitical realities.

3 On African megacities, see also Nawrot et al. 2017.