Future demographic trends and scenarios

by Massimo Livi Bacci

The main Euro Mediterranean regions are experiencing an unprecedented demographic transition. Analysing and managing this transition properly is key to developing solutions for the stability of societies on both shores of the Mediterranean.

A global demographic revolution

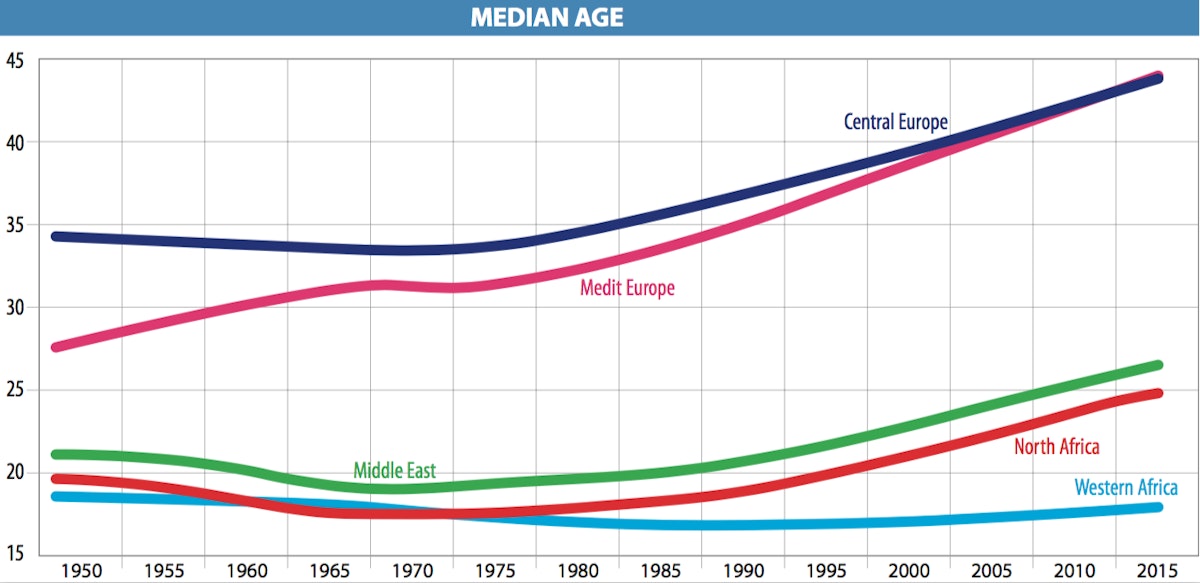

The world is in the midst of a revolutionary demographic transition and never in modern history has the distance between the main drivers of population change of the different regions of the world been so wide as it is today. In almost all developed countries, and in some emerging societies, fertility is far below the replacement rate, and life expectancy at birth is 80 years or more. In Europe, in a zero-migration scenario and with birth rates held constant, 33 out of 40 countries would experience population decline before mid-century. In countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, on the other hand, the average number of children born per woman is around 5, the availability of birth control is often limited to small urban élites, survival is precarious, and life expectancy in some countries is below 50 years. The population of Africa will more than double before 2050. World geo-demography is also rapidly changing: in 1950, Europe accounted for 22% of the world population, but its weight was only 10% in 2015, and will decline to 7% in 2050. On the other hand, Africa had 9% of the world population in 1950 and 16% in 2015, and will exceed 25% in 20501. Different rates of growth – negative in many European countries, between 2 and 4% per year in the sub-Saharan Africa – are closely related to the age structure of the population. In Europe the median age of the population is close to 45, in sub-Saharan Africa less than 20.

The ongoing demographic revolution has profound social and economic implications. In mature countries of the north of the globe, population stagnation and decline, and ageing, may imply a slowdown of productivity and innovation, a growing burden on state budgets for social services, pensions and health; more investment in human capital; and more favourable opportunities for dealing with environmental issues. In the rapid-growth and very young populations, the real challenges are providing adequate nutrition, care and education to the rapidly growing younger generations; the creation of jobs - particularly in agriculture and manufacturing - for the expanding young labour force; and investment in productive infrastructures. Finally, demographic and economic divergences compound their effects and reinforce the push-pull forces which shape international migration flows.

Different patterns in European

and African regions

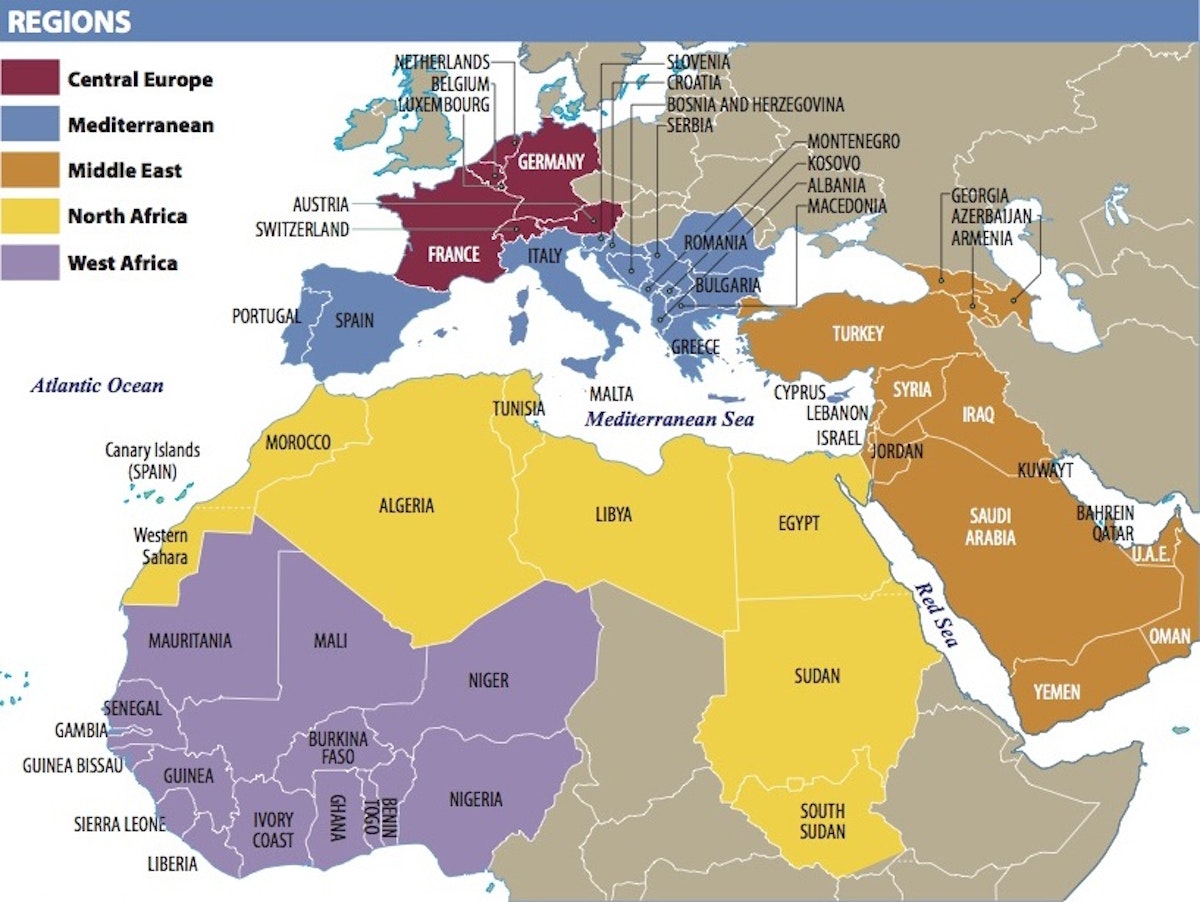

In order to gain a general view of main drivers of population change, it is useful to compare the trends of fertility, mortality and migration of five regions within which the push-pull forces which shape international migration operate andintersect. These five regions2 are: Central Europe, the powerhouse of continental Europe, dominated by France and Germany (whose combined population represents three quarters of the entire region); Mediterranean Europe, where Italy and Spain hold 70% of the total population; the Middle East, with Turkey accounting for one third of the total; North Africa, where Egypt, Algeria and Morocco have 75% of the total population; and Western Africa, dominated by Nigeria, where more than half of the total population lives. Those five regions contain 1.2 billion inhabitants, one sixth of the entire world population; each one of the five regions is relatively homogeneous as far as demography is concerned and shares some common economic, social and cultural features. Table 1 reports the population of the 5 regions in 1950 and 2015, and their annual rate of change over the period considered. Differences are dramatic: between 1950 and 2015 the population of the two European regions has increased between 30 and 40% (rate of growth close to 0.4% per year), while the population of the three other regions has increased by around 500% (rates of growth close to 2.5%); in 1950 six out of ten inhabitants of the five regions were Europeans, against three out of ten in 2015.

Past trends offer some guidance for the future: demographic phenomena are deeply entrenched in the history, culture, and social structure of a population, and changes are usually – with exceptions, of course – rather gradual.

Children per woman, 5 regions, 1950-2015 shows the mean number of children per woman (total fertility rate - TFR)3 for the five regions, from 1950-55 to 2010-15. Trends are clear: Western Africa has the highest level of fertility, with about 5.6 children per woman in 2010-15, only one unit below the mid-20th century level. Contraception is used only by a minority of couples, marriage age is very low, and almost all women enter a union or marriage. The two European regions have had fertility levels around 1.5 children per woman since the early 70s or early 80s, levels that imply a declining population. The Middle East and North African regions are similar to each other, showing a high fertility rate close to that of Western Africa in the 1950s, and a relatively sharp decline, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s, followed by a tapering off of the decline in the first and second decade of the present century.

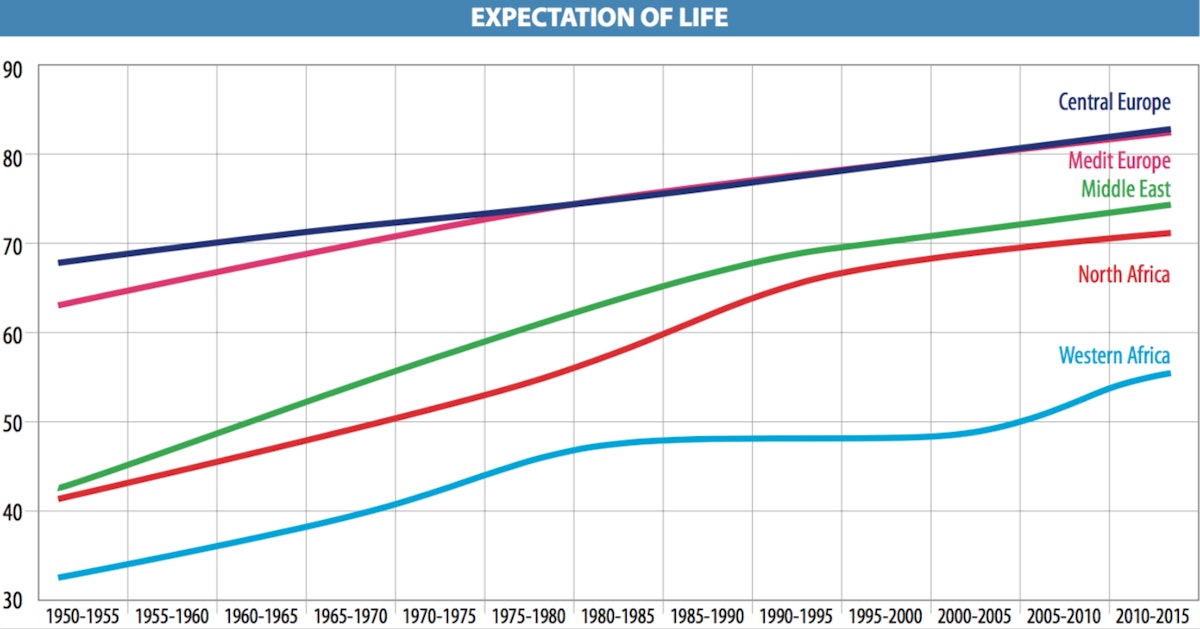

Expectation of life reports trends in survival, represented by the life expectancy at birth4: in each of the 5 regions progress has been continuous, except in West Africa where it stagnated in the 80s and 90s as a consequence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In the two regions of Europe, the curves have overlapped since the 1970s, and life expectancy at birth (for males and females together) is now well above 80, 15 years above the level of the 1950s. The line on the bottom is that of West Africa, which has gained 25 years over the period, but has a life expectancy 23 years below that of the European regions, and 15 years below that of Middle East and North Africa.

Net migration reports the volumes of net migration6 from 1950 to 2015.

Central Europe has attracted immigration throughout the entire period, with a net total of 22 million people. Policies have changed overtime, but the strong economy of the area, its relatively weak demography, and the openness of its societies have consistently attracted a relatively strong inflow of migrants. Mediterranean Europe, on the other hand, responded to the labour demand of the rest of Europe with high levels of emigration in the 1950s and 1960s; in the following decade net migration became positive, peaking in the first decade of this century (the balance has returned to negative in 2010-15 as a response to the financial crisis in Europe). The positive net migration of the Middle East area peaked between 2000 and 2015, mainly because of an inflow of refugees and displaced persons moving into the region from the east. The two African regions have lost population through migration over the entire period considered. Outflows have been larger in North Africa than in Western Africa.

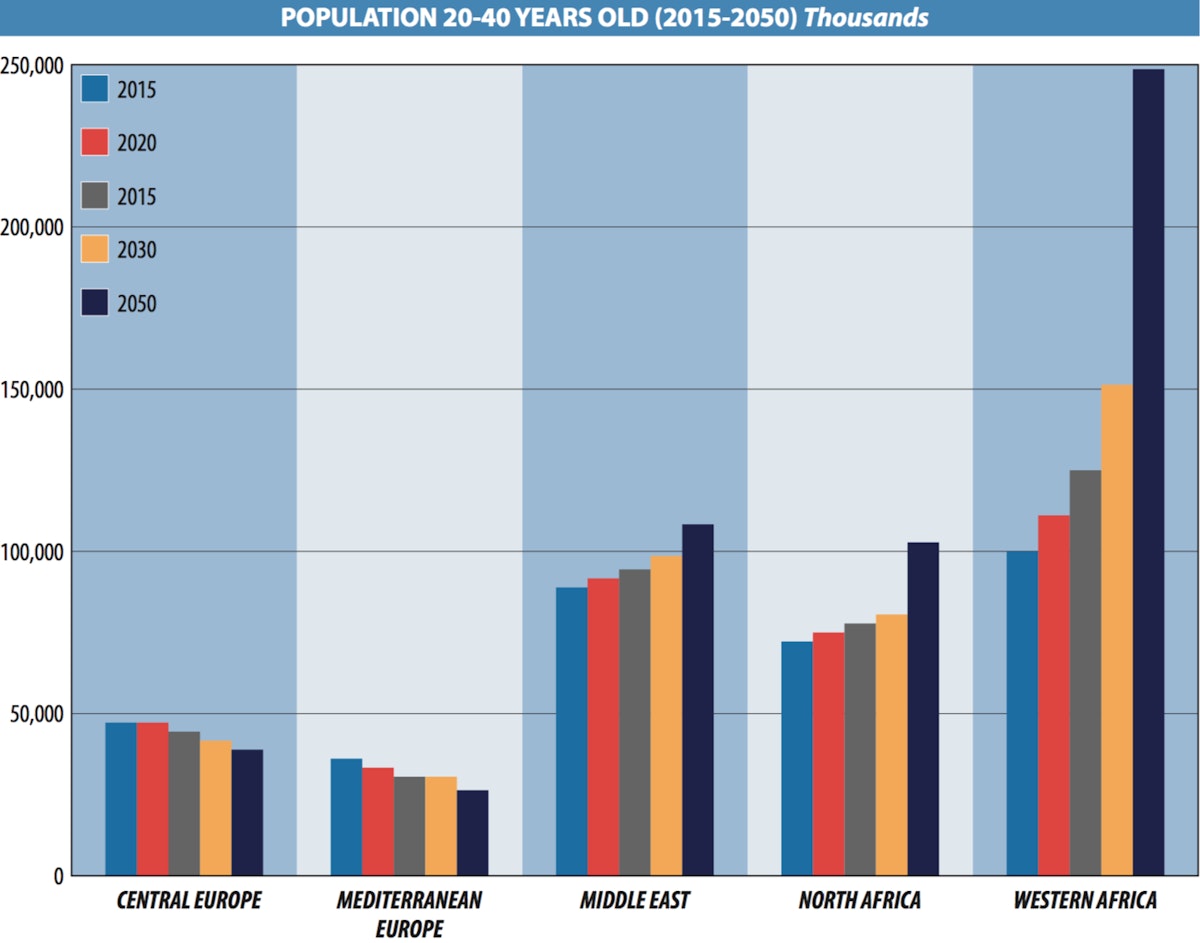

A hint at the future migration pressures in the various regions may be gained from Population 20-40 years old, 2015/2050, which shows the change of the population of 20 to 40 years old, from 2015 to 2050: a continuous erosion in Europe, a moderate increase in North Africa, an explosion in Western Africa. It is from this age group that the great majority of migrants is drawn, unable to find suitable jobs in their own country.

A demographic maelstrom

Within the five regions examined in the preceding pages, 13 countries have been selected as “major players”7 worth a closer look in order to get a more detailed vision. These 13 major players contain about two thirds of the entire population under scrutiny.

The main demographic indicators of the major players are reported in the next page. The main drivers of population change are indeed extremely variable in the area considered: fertility in Niger (7.6 children per woman) is almost 6 times that of Spain (1.3); longevity in Italy is 32 years longer than in Cote d’Ivoire; median age in Germany (46.2) is 31 years higher than in Niger (14,8), and the proportion of the population over 70 in Italy (16.3%) is twelve times that in Burkina Faso (1.3%). These data underline the demographic maelstrom created by the intersection of rich and poor societies in this area of the world. The divergent forces at work will determine the course of population change in the decades to come.

Population (thousands) of the major players, 2015-2050 reports the total population of the 13 major players, and their rate of growth in a short (2017-22), medium (2022-30) and long-term (2030-50) perspective. The hypothesis underlying the projection predicts a relatively feeble recovery of fertility in the European countries, and a continuation of the decline in the countries from the Asian and African continents; however, this decline is projected to be faster in the Western African countries that still have a very high fertility. As for survival, life expectancy is expected to continue its rise, steeper in the countries where it is low. In other words, the projection implies a slow, gradual convergence between countries.

Let us take the largest countries of Europe (Germany) and Africa (Nigeria): in the first, the number of children per woman is projected to rise from 1.4 (2015-20) to 1.6 (2045-50), and life expectancy from 81.5 to 86.1. In Nigeria, fertility is set to decline from 5.6 (2010-15) to 3.5 (2045-50) and life expectancy is set to increase from 53.7 to 62.3. The convergence hypothesis (whereby demographic trends, now so distinct, will become more homogeneous as development evens out the dramatic economic, social, and structural differences between countries) is plausible in the very long run, but less so in the short term, as it will be argued below.

In the short-to medium term, the rates of growth of the 13 countries show stagnation or a slight decline in the 4 European countries, and very high growth in the 5 West African countries, with particularly dramatic statistics for Niger, whose 4% growth rate - if sustained – would imply a doubling of the population every 17-18 years. Turkey, Egypt, Algeria and Morocco make up the middle ground with rates of growth coming in between 0.7% and 1.5% but projected to decline rapidly. One aspect of particular relevance for migration is the ever increasing share of young adults (20 to 40 years) in western African countries: taking Nigeria as an example, the part of the population aged 20-40 will increase 32.4% between 2020 and 2030, against 27% for the entire population.

Enhancing development to escape the Malthusian trap

There are many aspects of population change in the area under observation that are incompatible with long term balanced development, and that may produce negative externalities that require painful adjustments. The most evident one is the lack of governance of international migration. Other aspects concern fertility: too low in Europe, too high in Western Africa. History shows that high fertility may be reduced considerably with the right mix of social and economic policies; on the other hand, the nature and efficacy of policies aimed at raising fertility are controversial. In other words, increasing birth rates is far more difficult than bringing them down. A fertility rate of 1.4 – as in Germany, Italy and Spain - implies in the long run a rapidly shrinking and ageing population, which is unsustainable without the support of massive immigration. But the high fertility of West Africa (and of all the sub-Saharan area) is also unsustainable: if present trends continue, it would imply a trebling of the population in the three decades before mid-century. The reduction of fertility and of the rate of growth are therefore a high political and social priority.

High fertility may plunge populous areas into the Malthusian trap mentioned previously: poverty nourishes hunger, malnutrition and high infant mortality which, coupled with high fertility, produce a high rate of growth that generates even more poverty – a vicious circle. Interrupting this pattern was extremely difficult two centuries ago, when Malthus produced his work. However, modern economic, social and scientific capital can provide the means for breaking the cycle. Children’s health may be improved and malnutrition reduced, lowering mortality and increasing human capital. Adequate social policies may empower women and help couples to control their fertility and reduce unplanned births. Many countries in Western Africa have developed official policies to this end, but a lack of commitment at all levels (national and local, government and private, religious and civil) has compromised their realisation, far more so than a lack of resources.

High fertility is not the only driver of migration; it has been argued that although economic growth in the whole Sub-Saharan Africa has been relatively high, it has largely occurred outside the most labour-intensive sectors, like agriculture or manufacturing, that have been unable to absorb the growing young labour force. A decline of fertility will slow down the growth of this group and ease the pressure that leads to long run migration: in the short and medium term (say the next couples of decades) only enhanced development may lower that pressure.

In order to offer a more thorough understanding of development, interdependence, and human capital, in the next sections we will provide an analysis of climate change in the main five regions, and we will highlight and explain the key challenge of nutrition for human capital in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

1 In this section, the estimates of past population and projections for the future are based on United Nations, World Population Prospect. The 2015 Revision, New York, 2015. [ https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ ]. Projections are those of the “medium variant”.

2 Countries comprising each of the 5 regions are listed in Table 1.

3 The average number of children a hypothetical cohort of women would have at the end of their reproductive period if they were subject during their whole lives to the fertility rates of a given period and if they were not subject to mortality. It is expressed as children per woman.

4 The average number of years of life expected by a hypothetical cohort of individuals who would be subject during all their lives to the mortality rates of a given period. It is expressed in years.

5 The age that divides the population in two parts of equal size, that is, there are as many persons with ages above the median as there are with ages below the median

6 The net number of migrants, that is, the number of immigrants minus the number of emigrants.

7 The 13 “major players” are: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali, Cote d’Ivoire.